If you turned on the clock used by physicists at the birth of the universe, it would have by now – 13.8 billion years later – deviated from its true value by no more than 0.05 seconds. Thanks to this highly accurate measurement method, physicists were able to measure the effect of gravity on the passage of time, as described by two groups of researchers in the journal. temper nature†

This isn’t the first time this effect, known in professional circles as “gravitational redshift”, has been measured. But that has not yet been achieved as accurately as it is now.

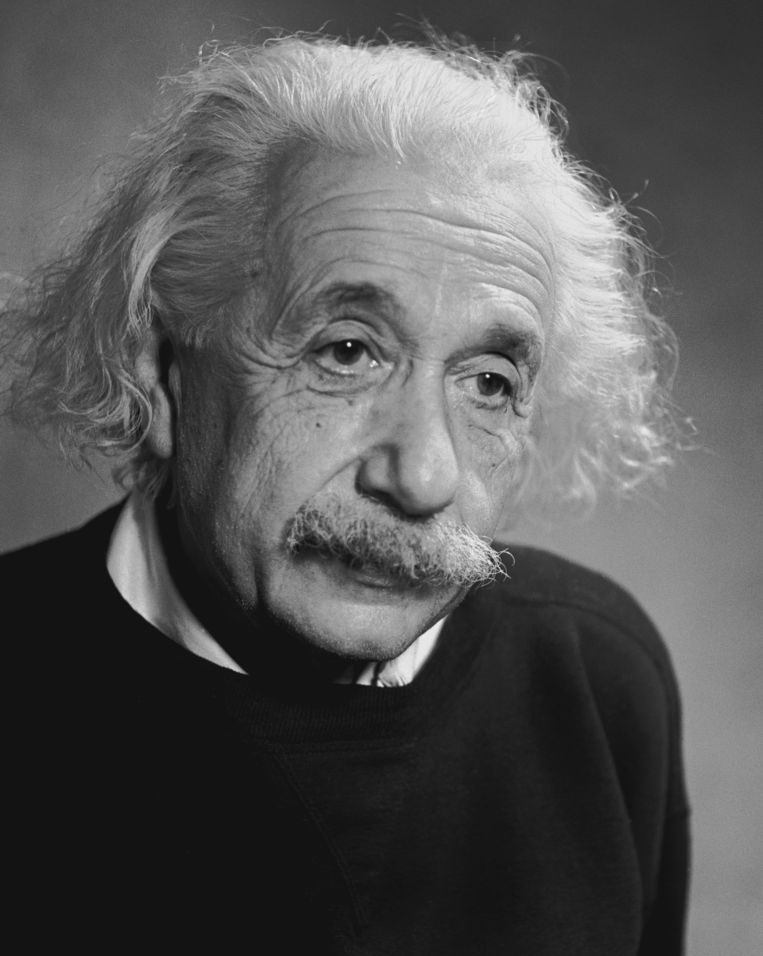

As early as 1976, physicists revealed in an experiment that Albert Einstein was right when he predicted in his theory of relativity that time slows down near massive masses. At the time, they did it with a very accurate clock in a spacecraft 10,000 km above Earth and one on Earth. At the end of the experiment, it was already found that the space clock ticks slightly faster than the one on the surface of the planet: by a difference of one second every 73 years.

This seems insignificant, but it is an effect that the GPS satellites, among other things, orbiting twice above the Earth, must constantly compensate for. If they do not, then determining their position, for example, our route planners will not be correct.

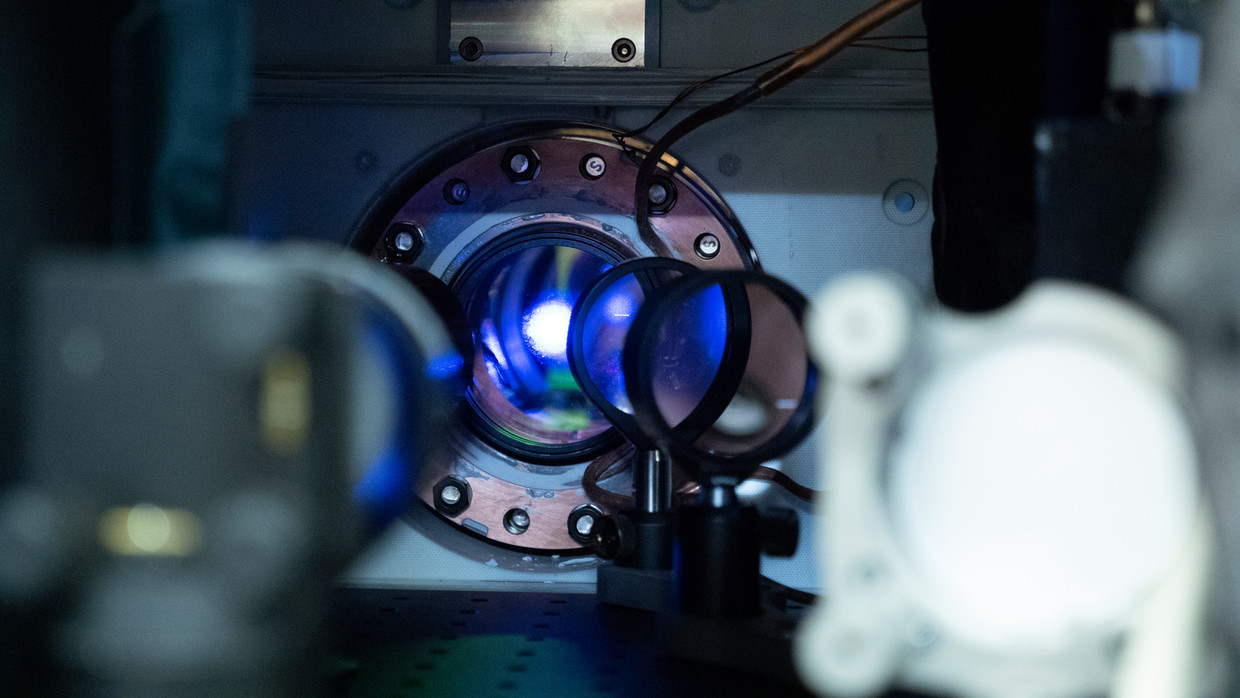

Atomic cloud in laser beam

The most accurate time counters that physicists know today are atomic clocks. Think not of the dial with a second hand, but of a “clock” that “ticks” thanks to regular changes in the energy states of atoms. By placing two of these atomic clocks directly on top of each other, in 2010, physicists were already able to measure gravitational redshift at a distance of one meter.

In the two new experiments, the preferential step is now taken, by not using two separate arrangements as clocks, but by comparing the time in (groups) of atoms within a single order. In this way, the physicists were able to measure the time difference between energy transitions in atoms a few millimeters apart on either side of a single atomic cloud suspended in a laser beam. In the second article, another research group described something similar, but between two clouds of atoms separated by a centimeter.

“Fantastic results,” says physicist Florian Schreck (University of Amsterdam), who also conducts research in ultra-precise atomic clocks. “It’s been in the air for a while for someone to do this. You can also see this in the fact that two research groups are now doing this simultaneously, independently of each other.”

Physicists want to use their technology for the long-term to gain new insights into physics, all of which are related to gravity. For example, they hope to reveal how this force works at the smallest particle level – an important open question in physics – and want to better map the shape of the Earth, again through gravitational measurements.

“Total coffee specialist. Hardcore reader. Incurable music scholar. Web guru. Freelance troublemaker. Problem solver. Travel trailblazer.”

More Stories

GALA lacks a chapter on e-health

Weird beer can taste really good.

Planets contain much more water than previously thought