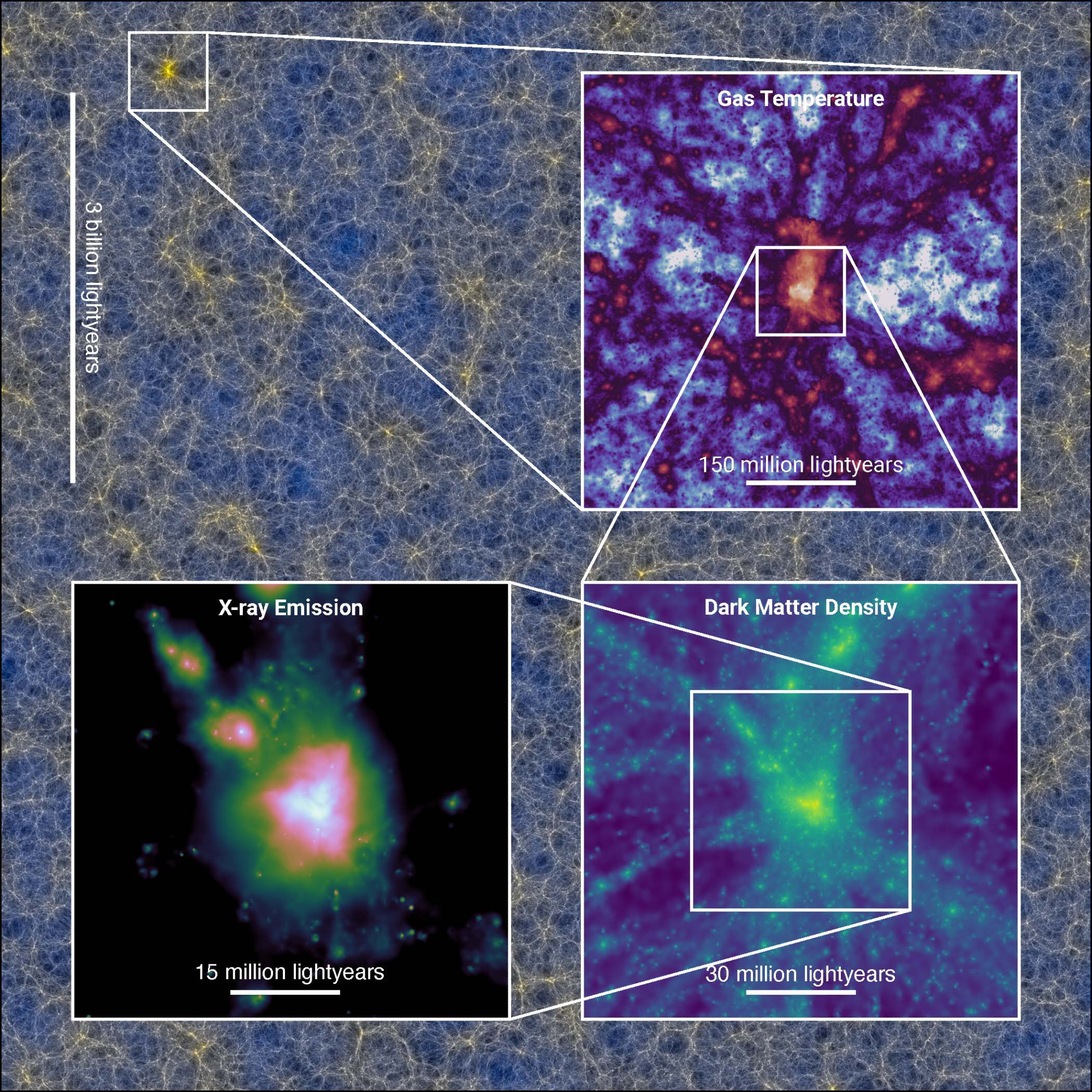

An international team of astronomers has conducted the largest cosmological computer simulation ever, tracking not just dark matter, but regular matter as well. The Flamingo simulation calculates the evolution of all components of the universe – ordinary matter, dark matter and dark energy – according to the laws of physics. As the simulation progresses, virtual galaxies and clusters of galaxies are created. The simulations required more than 50 million CPU hours and produced more than 1 petabyte of data. The results have been accepted for publication in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. The first three articles describe the methods, introduce the simulations and provide an initial look at possible ways in which the simulations could be used in the future.

Huge sums of money are being invested around the world in increasingly large telescopes on Earth and in space, such as the Euclid Space Telescope recently launched by the European Space Agency (ESA). These and other facilities collect huge amounts of data about galaxies, quasars and stars. Simulations like FLAMINGO play a key role in the scientific interpretation of data by linking predictions of theories about our universe to observed data.

According to the theory, the properties of the entire universe are determined by a small number of numbers, called “cosmological parameters” (six in the simplest version of the theory). The values of these parameters can be measured very accurately in different ways. One of them is based on the properties of cosmic background radiation, which is the thermal radiation left over from the Big Bang. But these values don’t all match those measured by other techniques that look at the way galaxies’ gravity bends light. These tensions may spell the end of the standard model of cosmology – the “cold dark matter model.”

Computer simulations may be able to explain the cause of these tensions because they can find potential systematic errors in the measurements. If none of these flaws are enough to defuse tensions, the theory is in real trouble.

The computer simulations to which the observations were compared have so far only tracked cold dark matter. “Although dark matter dominates gravity, the contribution of ordinary matter can no longer be neglected, because it can be compared with deviations between models and observations,” says research leader Job Schaie (Leiden University). Preliminary results show that both neutrinos and ordinary matter are needed to make accurate predictions, but they do not eliminate tensions between different cosmological observations.

Ordinary matter and neutrinos

Simulations that also follow so-called ordinary baryonic matter are more difficult and require much more computing power. This is because ordinary matter — which makes up only sixteen percent of all matter in the universe — feels not only gravity but also gas pressure, allowing matter to be ejected from galaxies by active black holes and supernovas far out into intergalactic space. The strength of these intergalactic winds depends on explosions that occur in the interstellar medium, and they are very difficult to predict. In addition, the contribution of neutrinos, which are subatomic particles with a very small mass but not precisely known, is also important. The motion of neutrinos has also not been simulated yet.

The transcript continues below the video

video

road

Astronomers have completed a series of computer simulations tracking the formation of structure in dark matter, regular matter and neutrinos. “The influence of the galactic wind was calibrated using machine learning, by comparing predictions from many different simulations of relatively small sizes with observed galaxy masses and gas distribution in galaxy clusters,” explains PhD student Roy Coghill (Leiden University). .’

The researchers simulated the model that best describes the calibration observations using a supercomputer at different cosmic sizes and with different resolutions. In addition, they varied model parameters, including the strength of the galactic wind, the mass of neutrinos, and cosmological parameters in simulations with slightly smaller, but still large, volumes.

The largest simulation uses 300 billion resolution elements (particles with the mass of a small galaxy) in a cubic volume with edges spanning ten billion light-years. This is the largest cosmological computer simulation of ordinary matter ever. Matthieu Schaller (Leiden University): “To make this simulation possible, we developed a new code, SWIFT, which efficiently distributes the computational work over more than 30,000 CPUs.”

Follow up research

FLAMINGO simulations open a new virtual window on the universe that will help make the most of cosmological observations. In addition, the large amount of (virtual) data creates opportunities to make new theoretical discoveries and further test new data analysis techniques, including machine learning. Using machine learning, astronomers can then make predictions for random hypothetical universes. By comparing them with observations of large-scale structure, they can measure the values of cosmological parameters. Furthermore, they can quantify the associated uncertainties through comparison with observations that quantify the influence of galactic winds.

Scientific articles in MNRAS

Project Flamingo: Cosmic Hydrodynamic Simulations of Large-Scale Structure and Galaxy Cluster Surveys, Job Shay et al.

Flamingo: Calibrating Large Cosmological Hydrodynamic Simulations Using Machine Learning, Roy Coghill et al.

The Flamingo Project: Rethinking S8 tension and the role of baryonic physics, Ian McCarthy et al.

website

Flamingo Project website With photos, videos and interactive visuals.

“Total coffee specialist. Hardcore reader. Incurable music scholar. Web guru. Freelance troublemaker. Problem solver. Travel trailblazer.”

More Stories

GALA lacks a chapter on e-health

Weird beer can taste really good.

Planets contain much more water than previously thought