France media agencyAugust 13, 2021, 2:29:00 PM KSA

The equivalent of walking around the world twice at the age of 28, the woolly mammoth whose steps researchers have followed has proven that the huge beast traveled long distances.

The results were published Thursday in the prestigious journal SciencesIt could shed light on theories about the cause of the extinction of the mammoth, whose teeth were larger than a human fist.

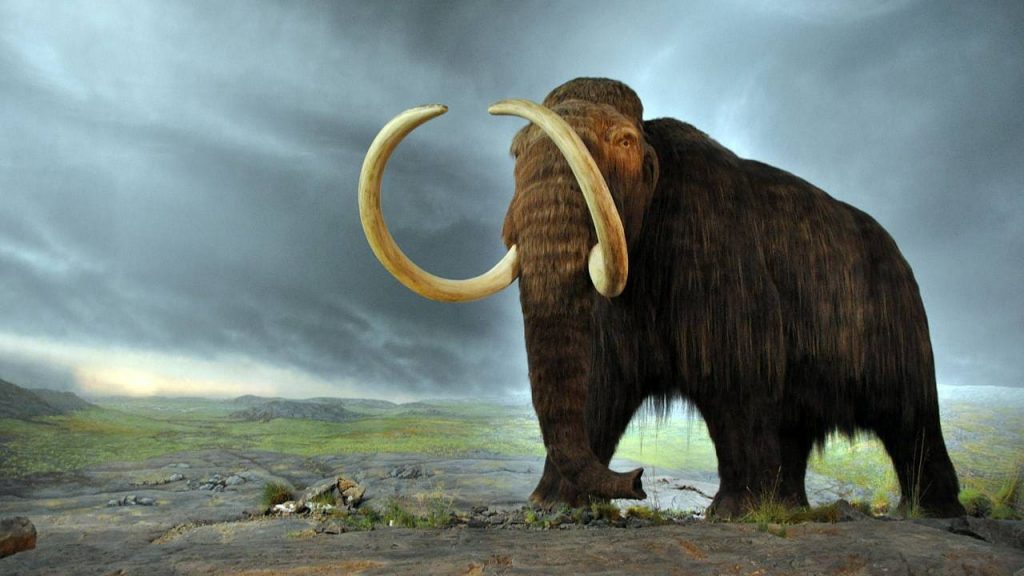

The giant scientists they studied may have traveled 70,000 miles and didn’t stay on the Alaskan plains as they expected. Image credit: Wikipedia

Clement Patai, associate professor at the University of Ottawa and one of the study’s lead authors.

He told AFP that there was no clear reason for mammoths to travel long distances “because they are a huge animal that takes a lot of energy to get around”.

The researchers were surprised by the results: The mammoths they studied may have traveled 70,000 kilometers (43,500 miles) and didn’t stay on the Alaskan Plains as they expected.

“We see it stretched all over Alaska, so it’s a huge area,” Patay said. “It was really a surprise.”

Readings on the tusk

For their study, the researchers selected the tusks of a male woolly mammoth that lived at the end of the last Ice Age.

The animal – named “Kiki” after a local river – lived relatively close to the species’ extinction, about 13,000 years ago.

One of the canines was cut in half to read isotope ratios of strontium.

Strontium is a chemical element similar to limestone and is found in soil. It moves to vegetation and when eaten, it is deposited in bones, teeth … or fangs.

Canines grow throughout the life of any mammal, the tip of which reflects the first years of life and the base in later years.

Isotope ratios vary depending on geology and Bataille has developed an isotopic map of the region.

By comparing it with data from tusks, it was possible to track when and where the mammoth was.

At that time, glaciers covered the entire Brooks Mountains in the north, the Alaskan Mountains in the south, and the Yukon River Plain in the middle.

The animal returns regularly to some areas, where it can stay for several years. But his movements also changed drastically, depending on his age, before he eventually starved to death.

During the first two years of his life, researchers were even able to notice signs of breastfeeding.

“What was really surprising was that after the teenage years, the isotopic differences started to get more and more important,” Patai said.

The mammoth “has made a gigantic voyage of 500, 600 and even 700 kilometers three or four times in its life, in the span of a few months.”

Scientists say the male may have been solitary, moving from herd to herd to breed. Or perhaps he was dealing with a drought or harsh winter, forcing him to search for a new area where more food could be found.

Today’s lessons?

Whether it’s because of genetic diversity or because of scarce resources, Patai said, “this species obviously needs a very large space” to live.

But at the time of the transition from the Ice Age to the Ice Age—when they became extinct—”the area shrunk as more forests grew” and “people exerted so much pressure on southern Alaska, where perhaps the movement of mammoths would be much less.”

Understanding the factors that led to the mammoth’s disappearance can help protect other critically endangered megafauna species, such as caribou or elephants.

With climate changing today and people often confining larger species to parks and reserves, Patai said, “Do we want our children to see elephants the same way mammoths see today in 1,000 years?”

“Thinker. Coffeeaholic. Award-winning gamer. Web trailblazer. Pop culture scholar. Beer guru. Food specialist.”

More Stories

Comet Tsuchinshan-Atlas is ready to shine this fall

Sonos isn’t bringing back its old app after all

Indiana Jones and the Great Circle is coming to PS5 in spring 2025