We haven’t thought of this before: Outside our atmosphere, solar panels are no longer obstructed by clouds or the change of day and night. What if we transferred that solar energy from space to the Earth’s surface?

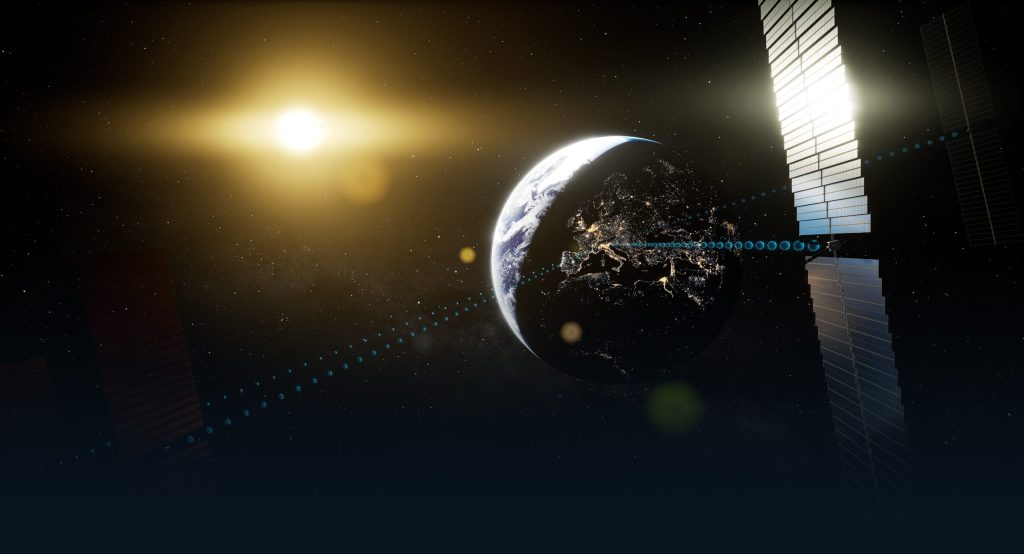

Enter Solaris, a brand new project from the European Space Agency in which the feasibility of space solar power will be studied in the coming years. And so our electricity may not come close from the solar panels on our roofs, but from much higher, from panels on giant solar collectors in distant orbit around our planet.

Although it sounds like a futuristic idea — the project’s name Solaris is not coincidentally also the title of a science fiction movie — it’s been around for a while. Satellites and space probes have been generating their own electricity for decades. As early as 1923, Russian rocket scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky pioneered a concept in which a network of large space mirrors would reflect sunlight and send it back to Earth’s surface in beams.

At the height of the (first) space boom, in the late 1960s, NASA engineers came up with a better way to transmit energy from space to Earth wirelessly: in the form of microwaves. The solar energy generated by the panels in space is first converted into microwaves, after which it is transmitted to a ground station on Earth. to be converted back into electricity there.

One advantage of microwaves, which are also used to carry communications signals, is that they are more penetrating to cloud cover. Because that, of course, is the great advantage of solar energy in space: not only is sunlight outside the atmosphere many times more intense than below the atmosphere, solar panels can be placed in space in such a way that they are constantly on – it’s already there all the time. “Goodbye”, with a non-stop radiant “Space Weather”.

How big is such a space solar collector?

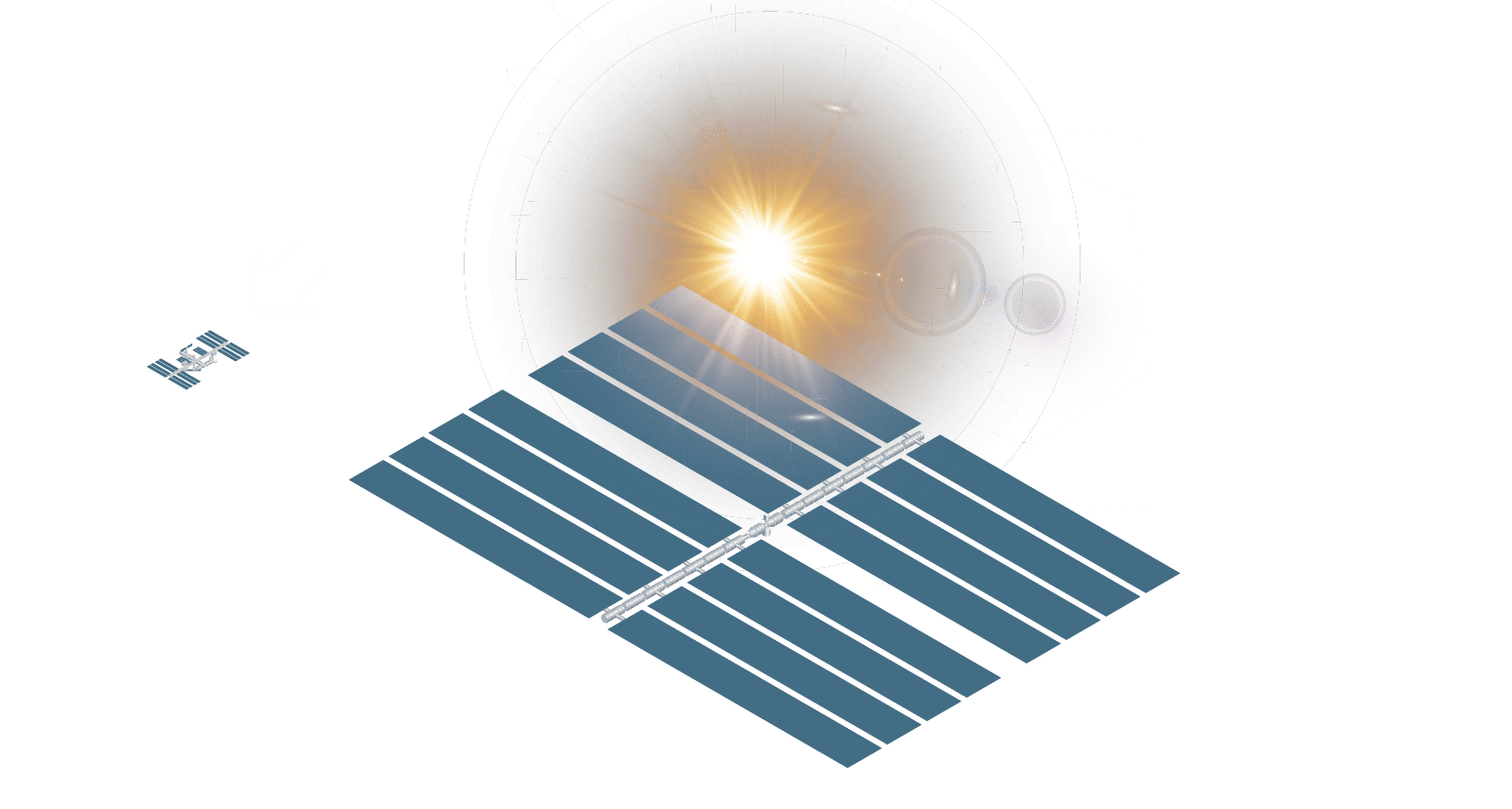

A single solar panel, or a series of panels assembled into a single solar collector, will span more than a kilometer and weigh thousands of tons. So it would take a lot of space missions (and launches) to put together a complex. This will not happen in low Earth orbit, where the International Space Station ISS is, for example, but in geostationary orbit, about 36,000 km from Earth. The advantage of this orbit is that an object in it rotates synchronously with the Earth, so that the relative position with respect to the Earth’s surface always remains the same. This orbit is also used by communications satellites for the same reason.

Comparison of the International Space Station (ISS) and a satellite with solar panels. The first will span about 100 meters (similar to a soccer field), and the second will be ten times as long.

How does energy reach the earth?

The fixed position relative to the Earth’s surface is necessary for the electricity generated from the solar collector to be sent to the ground station. This means that the direction of the microwave beam does not need to be adjusted every time. The microwaves are converted back into electric current by special antennas.

The fact that energy is transmitted through microwaves makes it possible to focus the energy beam to a certain extent, so that it falls only on a limited part of the Earth’s surface. After all, a focused beam is necessary to keep the transmission efficiency high enough. But if the focus is too narrow, the energy density can become very high, especially in the center of the beam. Exposure to them can be dangerous to human or animal life. Therefore, ground stations are likely to be built far from civilization, for example in deserts or at sea. This is why the Solaris project takes a closer look at transmission safety as well as technical and economic feasibility.

Ground stations will also extend significantly in the region. Since the energy beam cannot be perfectly focused on the Earth’s surface – solar collectors are too far away from it – the station must be at least ten kilometers in diameter.

“Total coffee specialist. Hardcore reader. Incurable music scholar. Web guru. Freelance troublemaker. Problem solver. Travel trailblazer.”

More Stories

GALA lacks a chapter on e-health

Weird beer can taste really good.

Planets contain much more water than previously thought