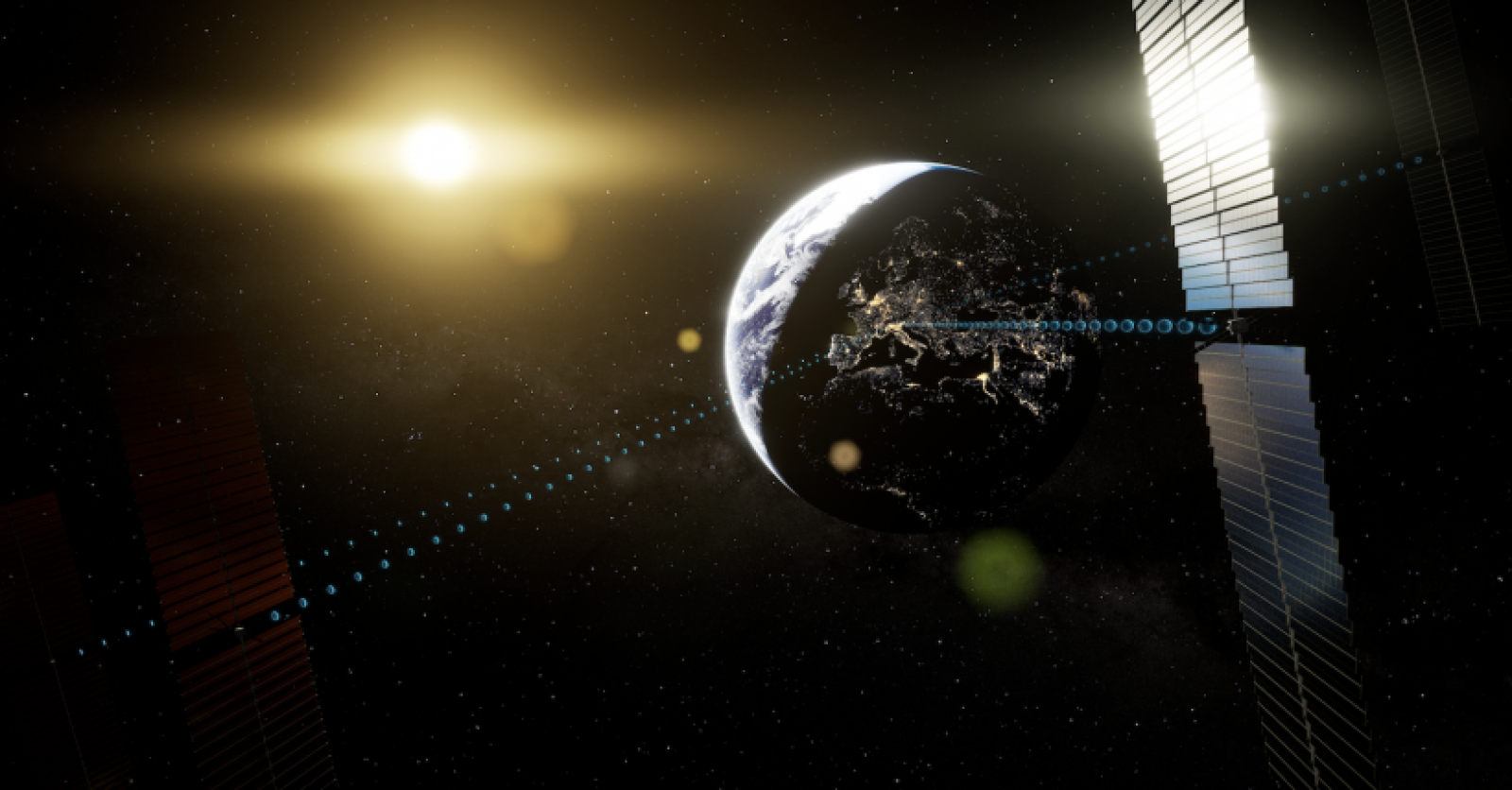

A decades-old promise will soon become a reality: unlimited solar power from space. The technical challenges and costs are enormous, but there is a lot to be said for this.

Solar panels in space or flying mirrors to illuminate dark parts of the world from space: in recent decades, these concepts have sometimes been taken out of the drawer, especially in times of rising energy prices. But in the end they were pushed aside. Putting all those solar panels or mirrors into orbit would be very expensive.

That could change now, at least according to the technology's supporters who hope to get “another arrow in the quiver of the fight against climate change,” as a US report on the subject says.

Research in the field of space power generation is conducted in the United States, Great Britain and Japan. The US Army is studying technology to supply power to remote bases. At aircraft manufacturer Airbus, they see a way to power planes during flight. China wants to launch a testing facility in 2028, two years earlier than originally planned. The European Space Agency (ESA) is currently conducting extensive research into the possibilities of this technology.

“The prices of solar cells and rocket launches have come down dramatically,” says Sanjay Vijendran. The Briton is head of the European Space Agency's Solaris project, which is based at the research and technology center in Noordwijk, the Netherlands. Vijendran previously worked there on Mars missions. You can say that the man loves crazy ideas. Vijendran sees this differently. “This is not esoteric science fiction,” Vijendran says of planned power plants in space. “Important players are looking at the possibilities in this area.”

Reusable rockets created by SpaceX founder Elon Musk have dramatically reduced transportation costs to space in recent years. The spacecraft that Musk is currently building could spark a revolution, although it has not yet successfully completed its maiden flight.

Last year, the European Space Agency conducted two studies into the economic feasibility of solar energy from space. The conclusion was that this process could in principle bear fruit by the 2040s, although it would require an investment of billions. But this also applies to new nuclear power plants, for example.

Two industry associations are currently writing reports for ESA. It should be available in November or December of this year. “This time, it is about the possible technical implementation of the test system,” says ESA employee Vijendran. What is striking is that in addition to the main contractors, the aerospace company Thales Alenia Space and the management consulting firm Arthur D. Little, the two major energy companies – France’s Engie Italy's Enel is also involved in the planning.

How it works?

Solar panels are sent into space by rockets and assembled into structures kilometers in size. Thin units such as carpet or tile structures may be introduced. It would make sense for the solar sails to fly at exactly 35,786 kilometers, because the satellites there orbit the Earth at the same speed as the Earth itself. This means that, as is usual with communications satellites, they are always above the same spot on the Earth's surface. This is important for the next step, where the energy that is converted into microwaves or lasers must be sent back to Earth.

However, the whole process is completely inefficient: every square meter of solar panels in a room receives about 1.4 kilowatts of sun. Even when the energy is converted to electricity, 70 to 80 percent will be lost, just as it is on Earth. In a space power plant, the loss would be even greater: Airbus experts estimate that converting to microwaves, whose wavelength is comparable to a Wi-Fi router, reduces efficiency by another five percent.

Airbus tested this process on a small scale last year. Two kilowatts of electricity had to be sent to Earth not from space, but from a distance of 36 meters in a hangar near Munich. At least 500 watts have already arrived. A few months ago, researchers at the California Institute of Technology sent an unknown but “verifiable” amount of energy from its Space Solar Power Demonstrator One small satellite to Earth from an altitude of 525 kilometers. Real estate billionaire Donald Brin left more than $100 million to the university to promote power generation in space.

However, there is still a long way to go before this concept can be implemented on a large scale. To generate one and a half to two gigawatts of electrical energy, solar cells will be needed covering an area ranging from 10 to 15 square kilometers in space. Hence, systems must be protected against space debris and ensured that it does not turn into dangerous junk at some point.

Risks to the ground?

Then there is the land use on the land. One receiving station must extend over an area of 70 square kilometers, depending on the frequency of microwave radiation used. For the antenna, a metal mesh, similar to a chain link fence, can be attached to above-ground masts. “70 square kilometers,” says ESA man Vijendran, “is the size of a German open-pit lignite mine.” Maybe we can turn one of them into a receiver.

But doesn't transferring large amounts of energy from space to Earth involve great risks? What about the birds that cross the crossbar – will they drop dead? How serious is the danger to people on Earth? Could the radiation concentrated here set everything on fire? Vijendran knows these questions and has answers ready. '250,250 watts per square meter is the highest power per surface area that can be expected on Earth when transmitting power from space. Although this value is higher than the human limit, the midday sun is stronger. Our body can handle it. The reception system should be equipped with warning signs, but this is not a reason for panic. Nobody catches fire, nothing gets fried. In winter, birds sit on their antennae to keep themselves warm.

How much should it cost?

One thing is clear: in the near future, power plants from space will provide much more expensive electricity than solar panels or wind turbines on Earth. “It's not about replacing wind and solar,” Vijendran says. “We want to create additional stock for periods when these sources are not available. At the same time, the need for long-term electricity storage will decrease.

These plans can best be compared to trying to generate energy through nuclear fusion. This process is also expensive and is only available in the medium term at best, but it is still a work in progress. Germany alone will spend more than a billion euros on this project over the next five years, partly because some basic technical issues still need to be clarified.

On the other hand, proponents of space solar power claim that the technical aspects have been clarified. “There's nothing left to be invented,” says Andrew Wilson of the Advanced Space Concepts Laboratory at the University of Strathclyde in Scotland. However, transportation to space would be expensive.

Elon Musk: “The stupidest thing ever.”

Among the experiment's critics, one voice is particularly surprising: SpaceX founder Elon Musk has called solar power from space “the dumbest thing ever.” Musk declared a few years ago that if anyone was in favor of producing solar energy in space, it should be him. “I have a rocket company and a solar company. I should be excited. But it is very clear that it will not work. This process is highly inefficient,” says Musk. According to him, installing additional solar cells on the ground would make more sense.

In about two years, the Europeans will decide whether to pursue their plans to generate power in space. ESA member states must then vote on whether to make funds available for a test mission. This may begin at the beginning of the new decade. “It's about something that can be launched all at once and doesn't have to be assembled in space,” says project leader Vijendran.

The system he envisions should have a capacity of one megawatt. The solar panels on the International Space Station, which are roughly the size of half a football field, currently produce only about 0.2 megawatts. But by Earth standards, the test facility's output will be small: power plants in the German port city of Hamburg alone have an installed capacity of about 600 megawatts, while those in Bavaria have an installed capacity of more than 33,000 megawatts.

So it is possible that Elon Musk and the critics will eventually be proven right, and that large-scale power generation in space will be postponed once again.

“Total coffee specialist. Hardcore reader. Incurable music scholar. Web guru. Freelance troublemaker. Problem solver. Travel trailblazer.”

More Stories

GALA lacks a chapter on e-health

Weird beer can taste really good.

Planets contain much more water than previously thought