There the professor suddenly became angry. He had taught the climate change lecture many times before, but now it had become too much for him to handle. He filled out the lecture and had to cancel the lecture. Just a glass of water.

It was a “defining moment” afterwards, says Eric van Sybel (42), the professor involved. That’s why he spoke about it in his inaugural address as Professor of Oceanography and Public Engagement, earlier this month at Utrecht University. Not because it was at that moment that he understood for the first time how much climate change actually affected him – but mainly because of what he noticed in his students.

They were deeply affected.

About the author

Martin Keulemans, Science Editor De Volkskrant, specializing in microlife, climate, archeology and genetic engineering. He was named Journalist of the Year for his reporting on the Coronavirus.

“I did not at all expect this from myself, nor did I intend to play on emotion,” he said afterwards, under the roof of the System, Six in the Back of the League. But then came the moment when I stopped the lesson because I couldn’t take it anymore. And I noticed: this has an effect.

You present it as something to be proud of. You can also say: That was a weak moment for me.

Scientists are people too. And I think we have to show that we’re not robots, that we have feelings, and that’s one of my core values. If we, as scholars, want to convey a story, it is not just about content. It’s also about passion.

Can You Put Your Finger On It: What Grips So Deeply About Climate Change That You Can Literally Cry About It?

“It’s because of sea level rise. The changes in the oceans that we’re seeing. The ecosystems that are completely changing there. The Arctic, with the sea ice melting there. The fishermen who are wondering: What fish am I going to catch in five years, and what should I prepare for?” ?

But for me personally, the main thing is that I feel guilty about it. Guilty of being in this position. I’m Dutch. I got my education, and I got support in my life. It is all based on an economic model of growth that is simply unsustainable. Because of the choices we make, future generations can no longer make all the choices they want. We close the doors to other generations. I wasn’t raised religiously at all, but we’re actually imposing some kind of original sin on posterity.

He is by no means an angry whiner. Here’s the scientist who once instructed his students to write a Wikipedia page on an oceanographic subtopic instead of an article, and who abruptly quits the podium during his introductory speech as a professor so he can interact more with people.

He gained worldwide fame eight years ago, when he was working in Sydney and the Malaysian passenger plane MH370 disappeared. And suddenly the world press discovered him as an expert on the sea current who could explain how scattering debris can be and why you can’t survey the sea floor with a satellite (he explained that the ocean is impenetrable to electromagnetic radiation). Suddenly a smooth-talking oceanographer appeared everywhere. “At one point I was in the studio with CNN for seven days straight,” he says, visibly happy.

That was before Van Sybel returned, after the Gulf Stream, to the Netherlands. One of his exciting new ideas is the project of tracking floating plastic back to its owner. “I have no idea if that will work,” he says right away.

But suppose it were possible, with the efforts of marine biologists, lawyers, and ocean experts, to trace the stranded pieces of plastic back to the ship that threw them overboard. “Then you might be able to hold the polluter jointly responsible for cleanup, as is also the case with oil spills,” he thinks.

Moreover, he has never been a climate activist. He says it’s rather “a bit of corporate” and “more of a green thing.” Someone who appreciates the black academic dress because it radiates dignity, tradition, and scientific impartiality. He only had a secondhand idea of climate change when he began studying physics to understand more about ocean currents.

You may now be the world’s first professor of oceanography and public engagement. What’s more: an oceanographer who just loves to communicate?

“The big difference is that I really want to do research with my group on: what works? We are increasingly asking our scientists to communicate, but there is still a serious lack of evidence-based theories about how to do it more effectively. Does the professor always speak or is the best Leave it to a university lecturer or a student?Which audience should you target?Readers De VolkskrantOr are you wearing more football inside or Linda? And how much effort is required to reach it?

We have to say “climate emergency” right here at your university right now, under pressure from student climate activists.

“Well, wait, you don’t have to do anything. The Executive Board here doesn’t dictate the words we use and don’t use. Above all, our board said: we’re adding the word ’emergency’ to the toolbox. In fact, the board recognizes that there are situations You could say: There is now a climate emergency.

You yourself constantly refer to the “climate crisis”. How does this relate to the neutrality of science that you praised a moment ago when we talked about the emergence of academic uniforms?

‘Did you say that?’ Perhaps you meant more: value. When scientists wear this robe, they radiate that they represent the same scientific values.

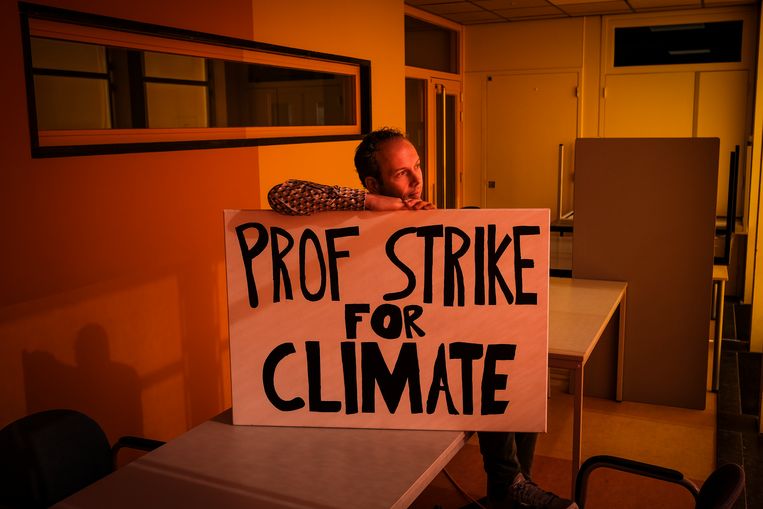

But you emphatically present yourself as a climate activist. You indicated in your interview that you are a vegetarian. And you were waving a sign: “Professor strikes for the climate.”

I’m not a member of Extinction Rebellion or anything, I played a bit too. But what you hear a lot, and it’s of course a very good comparison: No one thinks it’s weird when a pulmonologist says people should stop smoking. I think that’s similar to a climate scientist saying: We have to go to zero CO2 emissions, because if we don’t, we’re going into a future of… Well, humanity won’t die out, but there will be a lot, very big changes happening.

The difference is: how the body reacts to smoking, and doctors have seen it often enough. But no one knows how society will adapt to the effects of global warming.

No, but we know that if we continue down the path of greenhouse gas emissions, society will soon face a major challenge. Better to avoid it. Because in this way you give the future society more freedom, and do not direct it in a certain direction.

The point is also: can we still trust you when it comes to applying nuances? Would you say it honestly if, for example, the bad news about the climate turned out to be better than expected?

‘Yes, of course. First of all, I am a scientist. My inner motivation is this: wanting to understand how the oceans and climate work. And I think we really need more positive climate news. I’ve done a little bit of all of these doomsday scenarios myself.

Giving my introductory lecture, I stood for five minutes telling a story about how dramatic it was. But in the meantime I saw the people in the room and my neighbors and others were a little afraid. I think all of those Doom and gloom It is also one of the weaknesses of current climate communications.

Even louder climactic dramas not working?

These are exactly the questions we want to investigate: What works, what doesn’t, and when?

It turns out that the vast majority of Dutch people understand perfectly well that the climate is changing due to human activities Recently from the Social and Cultural Planning Office report. They just find other problems more pressing. There is even a certain aversion to climate advent: 55 percent want government not to meddle in their environmental choices, and a quarter are annoyed by all the climate concern. You must have an idea: How can you reach these people?

If such an undercurrent begins to emerge, it may make sense to communicate more from a positive perspective. And he will say: this also provides really great opportunities. If we go through this shift, it also means: less pollution, more green space, more biodiversity and, hopefully, a fairer world.

At sea, these are often issues that have nothing to do with climate change: overfishing, pollution, noise, and plastic. Why would you settle it to: climate?

“Because I think this is the best way to change society for the better Zero carbonPerhaps a society that no longer emits greenhouse gases is in many ways a circular society and people think about using raw materials in a good way.

In addition, there is already a lot of interest in the climate. This makes it a good way to get the message across. If this board I brought to my lecture read: A pro-ocean noise pollution strike(noise pollution at sea, Mr. Dr.), such an impression would not have been made for a long time.

He recalls a joke popular in climate circles, he says, about a climate skeptic jumping to his feet during a climate summit and angrily exclaiming: “What if climate change Trick Is one big trick? Then we improve the world for nothing! ”

Van Sybel points to the storyboard he took with him to his inaugural lecture and now hangs proudly on the wall in his office. “Oh, dude. I’d be so glad if this council could go so far and I could get back to my questions about the ocean. That in ten years no one will be sitting here at the table asking me about climate activism.

Do you mean that?

really and really. That’s why I liked the concern about the MH370 so much. This was because it was difficult to find a plane in the ocean. It wasn’t about the climate at all. Tasty.’

“Total coffee specialist. Hardcore reader. Incurable music scholar. Web guru. Freelance troublemaker. Problem solver. Travel trailblazer.”

More Stories

GALA lacks a chapter on e-health

Weird beer can taste really good.

Planets contain much more water than previously thought