Exotic diamonds from an ancient dwarf planet in our solar system may have formed shortly after the dwarf planet collided with a large asteroid about 4.5 billion years ago.

A team of scientists said they have confirmed the presence of lonsdalite, a rare hexagonal form of diamond, in ureylite meteorites from the mantle. dwarf planet.

Lonsdaleite is named after the famous British crystallologist Dame Kathleen Lonsdale, who became the first woman to be elected a Fellow of the Royal Society.

Research team – with scientists from Monash Universityand the RMIT . Universityand the CSIROAustralian synchrotron, and University of Plymouth – I found evidence of how Lonsdalite formed in urelite meteorites. They published their findings on September 12 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). The study was led by geologist Professor Andy Tomkins of Monash University.

Lonsdaleite, also known as hexagonal diamond in reference to its crystal structure, is an allotrope of carbon with a hexagonal lattice, as opposed to the cubic lattice of traditional diamond. It is named in honor of Kathleen Lonsdale, a crystal scientist.

The team expected that the hexagonal structure of Lonsdalite atoms makes it harder than regular diamond, which has a cubic structure, said Dougal McCulloch, RMIT professor, one of the senior researchers involved.

“This study conclusively proves that Lonsdalite exists in nature,” said McCulloch, director of the Microscopy and Microanalysis Facility at RMIT.

“We also discovered the largest lonsdalite crystals known to date, down to a micron – much thinner than a human hair.”

The research team said Lonsdaleite’s unusual structure could help develop new fabrication techniques for superhard materials in mining applications.

What is the origin of these mysterious diamonds?

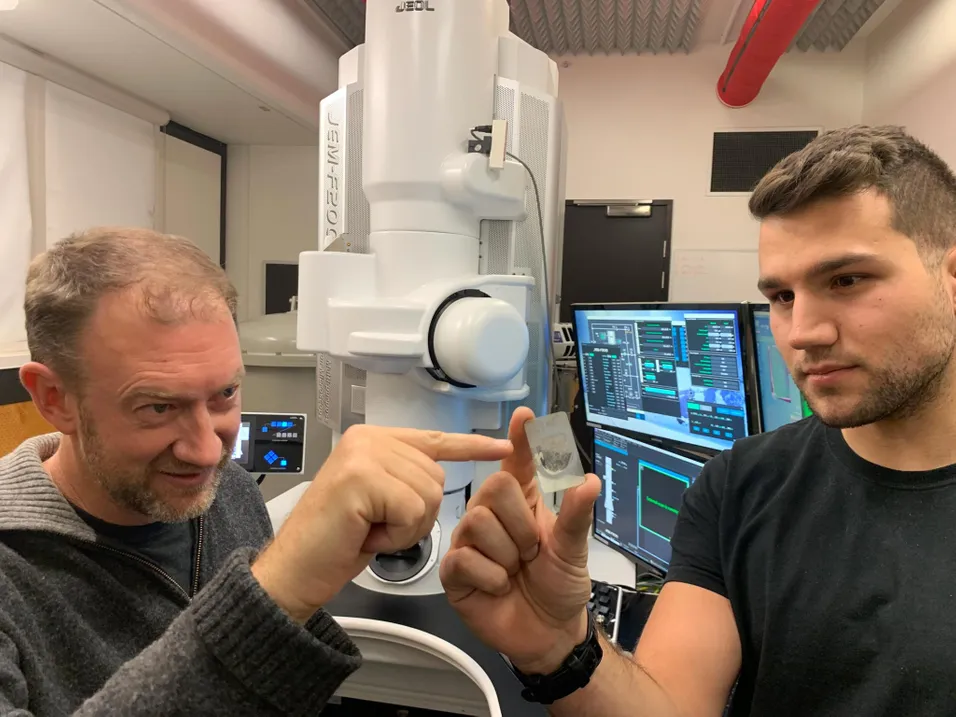

McCulloch and his team at MIT, doctoral students Alan Salk and Dr. Matthew Field, used advanced electron microscopy techniques to capture solid, intact slices of meteorites to create fast snapshots of how ordinary diamonds and diamonds formed.

“There is strong evidence for a newly discovered formation process of nisdalite and common diamond, which is similar to the supercritical chemical vapor deposition process that occurred in these space rocks, possibly on the dwarf planet shortly after a catastrophic collision,” McCulloch said. He said.

“Chemical vapor deposition is one way that people make diamonds in a lab, primarily by growing them in a specialized room.”

Professor Dougal McCulloch (left) and PhD researcher Alan Salk of RMIT with Professor Andy Tomkins of Monash University (right) at RMIT’s Microscopy and Microanalysis Facility. Credit: RMIT University

Tomkins said the group suggested that lonsdalites in meteorites consist of a supercritical fluid at high temperatures and moderate pressures, which preserves the shape and texture of pre-existing graphite almost perfectly.

“Later, Lonsdalite was partially replaced by diamond with a cooler, lower pressure environment,” said Tomkins, a future ARC fellow at Monash University’s School of Earth, Atmosphere and Environment.

And so nature has given us a process that we can try to replicate in industry. We believe that lonsdaleite can be used to make additional hardware machine parts if we can develop an industrial process that promotes the replacement of preformed graphite parts with lonsdaleite. “

Tomkins said the study’s findings helped solve a long-standing puzzle regarding the composition of the carbon phases in urelite.

The power of cooperation

Dr. CSIRO’s Nick Wilson said technology collaboration and experience from the various institutions involved allowed the team to confidently confirm lonsdaleite.

At CSIRO, a microanalyzer with an electronic probe was used to quickly map the relative distribution of graphite, diamond, and Lonsdalite in the samples.

“Individually, each of these techniques gives us a good idea of what this substance is, but when taken together, it really is the gold standard,” he said.

Reference: “Lonsdaleite sequence of diamond formation in Ureilite Trans Meteorites” Visible Chemical fluid/vapor deposition” by Andrew J. Tomkins, Nicholas C. Wilson, Colin McRae, Alan Salk, Matthew R. Field, Helen E. Brand, Andrew D. Langendam, Natasha R. Stephen, Aaron Turbie, Zanett Pinter, Lauren A. Jennings and Dougal J. McCulloch, 12 Sep 2022, Available here. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2208814119

“Total coffee specialist. Hardcore reader. Incurable music scholar. Web guru. Freelance troublemaker. Problem solver. Travel trailblazer.”

More Stories

GALA lacks a chapter on e-health

Weird beer can taste really good.

Planets contain much more water than previously thought