Mammoth, dodo, homing pigeon, Tasmanian tiger. Scientists have been trying to bring extinct animal species back to life since the 1990s. A team of researchers has shown that this is not so simple, with Study on March 9 at current biology figured out.

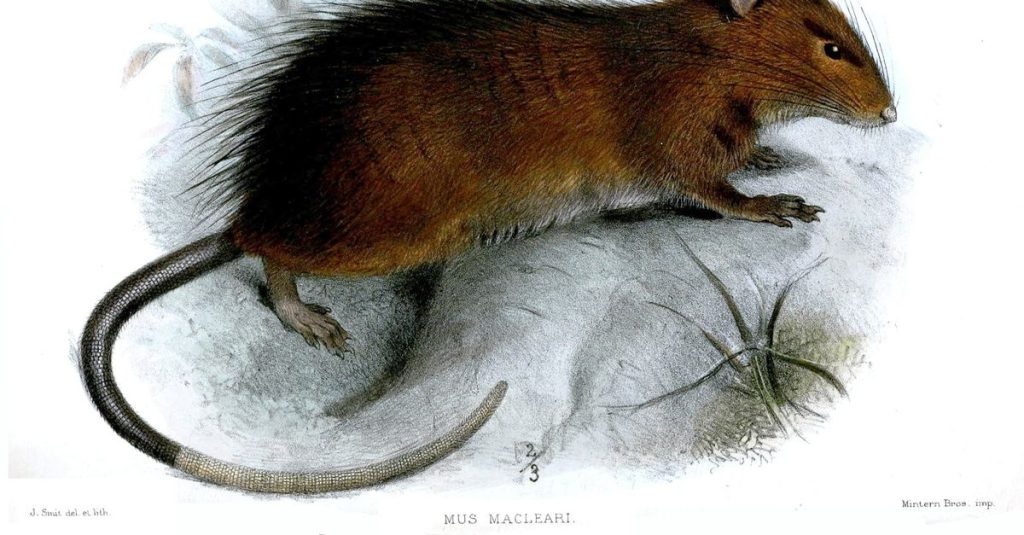

Scientists have turned their attention to Ratus McCleary, a reddish brown mouse roamed Christmas Island, an island in the Indian Ocean. The species became extinct between 1898 and 1908, presumably due to an infectious disease of the Norwegian brown rats that came aboard European ships.

The research team extracted DNA from two dry skins of extinct mice from the Oxford University Museum’s collection and mapped the genomes. “If you sequence the genome, current technologies give you a lot of separate pieces of DNA that you have to piece together,” says Naturalis evolutionary biologist Barbara Gravendel. “To put together the puzzle, you usually use an example. If a species is no longer alive, you will not have a complete example and it will be much more difficult to determine the DNA sequence. The scientists have well shown that this is not due to the age of the DNA, but to the lack of a reference.”

Commonly used lab animal

For lack of a better example, the team used the genome of the Norwegian brown rat as a reference. The rat shared an ancestor with an extinct species on Christmas Island 2.3 million years ago, making it its closest living relative. Because it is a commonly used laboratory animal, this genome is well known.

Although almost the entire genome of the extinct animal could have been mapped, five percent of it turned out to be untraceable. It was surprising that these genes did not spread over the genome. The majority seem to be related to the sense of smell and the immune system.

Genetic engineering is one of three ways, besides cloning and re-breeding, researchers are trying to bring extinct species back to life. In theory, scientists can compare the genomes of extinct species with the genomes of living species. The parts in the genome of living species that do not match are then modified using CRISPR technology. The Christmas Island Rat is an interesting case because it differs so much from the Norwegian brown rat as the elephant is from the mammoth. One of the species that scientists are trying to recover.

Quite a few

“If you’re going to use CRISPR to change the genome of a brown rat into the genome of a Christmas Island rat, you can’t change the immune and olfactory genes,” Gravendel says. “After all, you don’t know how it should be.” This is why in a best-case scenario – if you succeed in making the brown rat act as a surrogate mother for the Christmas Island rat – you will get a hybrid specimen. “After a few generations, that little bit of Christmas Island DNA has already disappeared from your population.”

There are more technical problems. In order to breathe new life into a species, you need quite a few genetically different animals. This also requires multiple copies of an extinct species. In many cases there is none. In addition, it remains to be seen if these new animals can ever survive in the world as it is now. Gravendeel: “The Christmas Island Rat died out relatively recently, but due to climate change, the island will now look very different.”

A version of this article also appeared in NRC Handelsblad on March 15, 2022

A version of this article also appeared on NRC on the morning of March 15, 2022

“Total coffee specialist. Hardcore reader. Incurable music scholar. Web guru. Freelance troublemaker. Problem solver. Travel trailblazer.”

More Stories

GALA lacks a chapter on e-health

Weird beer can taste really good.

Planets contain much more water than previously thought