In the entire Russian capital, there are significantly fewer men in restaurants, shops and social gatherings. Many of them were called up to fight in Ukraine. Others have just fled to avoid conscription.

The Chop Chop barbershop in the center of Moscow was always crowded on a Friday afternoon, but at the beginning of last weekend, only one of the four seats was occupied. “Normally we would be full by now, but about half of our customers are gone,” said the manager, a woman named Olya. Many clients – including half of the hairdressers – have fled Russia to evade President Vladimir Putin’s campaign to mobilize hundreds of thousands of men for the lax military campaign in Ukraine.

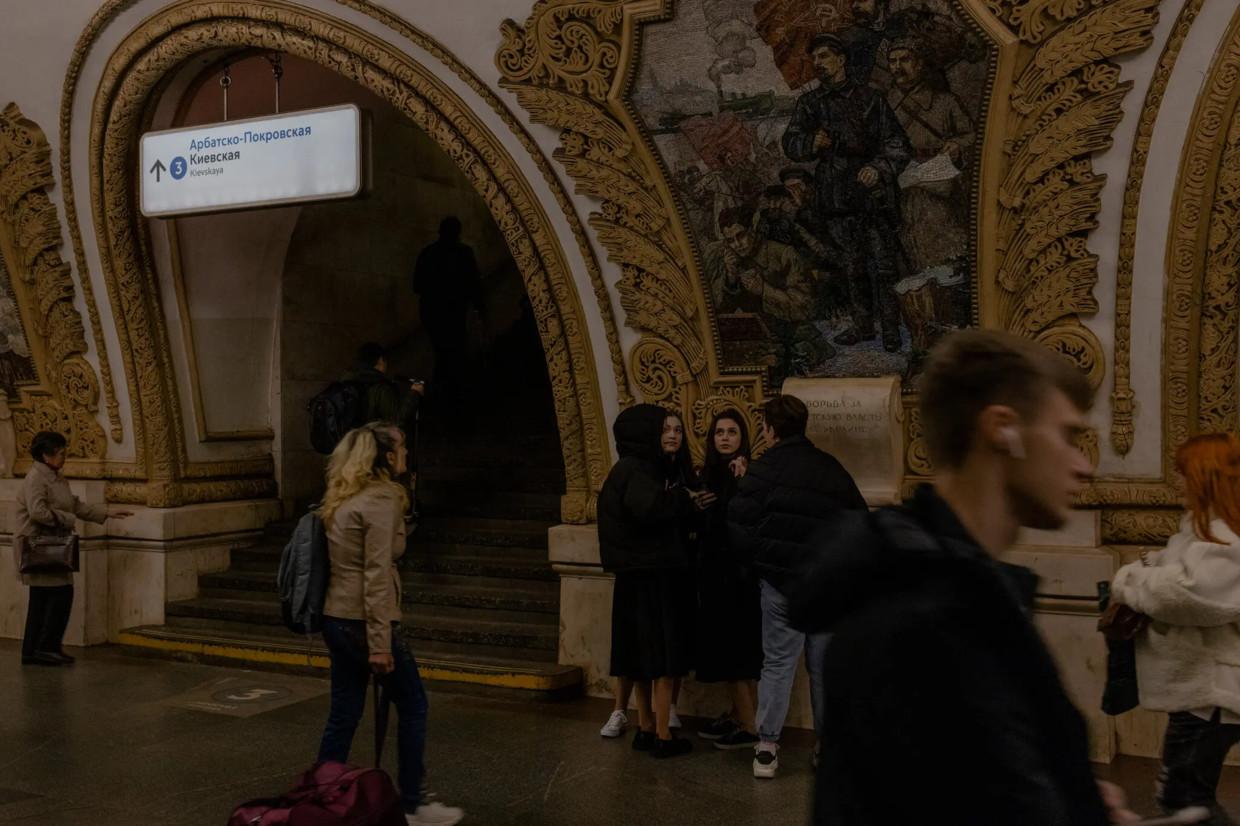

Many of the men remained inside, fearing that they would be called up for conscription. When Olya came to work last Friday, she saw authorities checking documents at each of the four exits of the metro station. Her boyfriend, who was a hairdresser at the salon, also ran away, and the divorce took a heavy toll. “Every day is hard,” says Olya, who, like the other women interviewed, does not want to use her surname for fear of reprisal. “It is hard for me to know what to do. We have always planned everything as a couple.”

She is definitely not alone. While there are still many men in a city of 12 million people, their presence has decreased significantly – in restaurants, in the hipster community, and at social gatherings such as dinners and parties. This is especially true of the city’s intelligentsia, who often have income and passports available to travel abroad.

Partial packing

Some male opponents left to invade Ukraine at the outbreak of war; Others opposed to the Kremlin generally fled for fear of capture or persecution. But most of the men who left in recent weeks had been drafted to serve in the army and either wanted to avoid conscription or feared Russia would close its borders now that Putin had declared martial law.

No one knows exactly how many men have left since Putin announced “partial mobilization,” but hundreds of thousands of men have. On Friday, Putin said that at least 220,000 men had been recalled.

At least 200,000 men have gone to neighboring Kazakhstan, where Russians can enter without passports, according to authorities. Tens of thousands of other people have fled to Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Israel, Argentina and Western Europe.

“I feel like we are now a country of women,” Stanislava, a 33-year-old photographer, said at a birthday party attended by mostly women. “I was looking for some male friends to help me move some furniture, and I realized they were almost all gone.”

Good-bye

Many married women remained in Moscow when their husbands fled, either after receiving a povestka – a summons – or before one of them could arrive.

“My friends and I get together to drink, talk and support each other, to feel that we are not alone,” said Lisa, 43, whose husband is a lawyer for a large multinational company, a few days before Putin. Announced received a call. He quit his job and fled to a Western European country, but Lisa stayed because their daughter goes to school and all of her grandparents are in Russia.

Women whose husbands have been called often have lonely time before them, but the feeling of loneliness is overshadowed by the fear that their husbands may not come back alive. Last week, wives, mothers and children gathered at a voenkomat, or military commissariat, in northwest Moscow to say goodbye to loved ones who had been sent to the front.

“These guys are like toys in children’s hands,” said Ekaterina, 27, whose husband Vladimir, 25, was inside collecting his rations and was about to take him to a training camp outside Moscow. “It’s just cannon fodder.” She wished he would have evaded the summons, saying it would have been better for him to spend a few years in prison than to come home dead.

Empty strip clubs

While Muscovites were able to enjoy a fun summer when it seemed as if nothing had fundamentally changed since the invasion of Ukraine, the situation is very different with the onset of winter and the effects of war, including sanctions, becoming more apparent.

On Monday, the mayor of Moscow announced the official end of the mobilization in the capital. But many companies have already felt a setback. In the two weeks following the call, orders at Moscow restaurants fell 29 percent from the same period last year. Kommersant newspaper reported that Sberbank, Russia’s largest bank, closed 529 branches in September alone.

Many downtown malls are empty, with “FOR RENT” signs in front of the windows. Even Russia’s largest airline, Aeroflot, has closed its office on the posh Petrovka Street. Nearby, shop windows are finally covered as Western designers have been changing their statues all summer.

“It reminds me of Athens in 2008, during the financial crisis,” said Alexey Ermilov, founder of Shopshop. Ermilov said that among the 70 barbershops in his own right, Moscow and St. Petersburg feel the absence of men the most. This is partly because more people have the means to leave.

Local media have reported that attendance at one of Moscow’s largest strip clubs has fallen by 60 per cent, and that there are fewer security guards available due to either being mobilized or fleeing.

Available men

Meanwhile, downloads of dating apps have increased dramatically in countries where Russian men have fled. In Armenia, the number of new registrations on Mamba, the dating app, increased by 135 percent, a company representative told RBK, a Russian news magazine. In Georgia and Turkey, the number of new downloads exceeded 110 percent, while in Kazakhstan it increased by 32 percent.

“All sane men are gone,” said Tatiana, a 36-year-old tech salesperson, watching a game of pool with her friends in a sorority on trendy Stoleshnikov Alley. “The dating pool Shrink at least 50 percent.” In the summer, the alley was still full of young Russians wanting to enjoy themselves. But last Saturday night was relatively empty. Tatiana said many of her clients had left, but she planned to stay. Her job doesn’t allow remote work And she didn’t want her big dog on a plane.

On the other hand, other Muscovites are still planning to leave. Alyssa, 21, another sorority member, said she just graduated and wanted to save enough money to leave Russia once her friends finished their studies. So that they can rent a house abroad together. “I don’t see any future here in Russia, at least not while Putin is in power.”

For the men who stayed, moving around the city became nerve-wracking. “I try to drive everywhere because on the street and next to the subway they can issue subpoenas,” said Alexander Peribalkin, director of marketing and editor of Blueprint, a fashion and culture publication.

Pereblkin remained in Russia because he felt obligated to his more than one hundred employees to keep the company going. But his offices now remind him of the early months of the Corona pandemic because of all the missing people. He and his business partners don’t know what to do. “Marketing is the kind of business you do in ordinary life,” he said in a posh café, but not in wartime, A space for teamwork. The cafe was almost completely filled with women, including a group celebrating a birthday with a flower arrangement class.

In the hair salon Chop-Chop, the founder Ermilov said something similar. He left for Israel at the end of September and is now planning to open a company that has no physical presence in his home country and is “less exposed to geographical risks.” In Russia, managers of hairdressers discussed the possibility of expanding services to female clients. “We are talking about reorienting the company,” said Olea, the manager. “But it is impossible to plan now, now that the planning horizon has changed to about a week.”

© 2022 The New York Times Company

“Creator. Award-winning problem solver. Music evangelist. Incurable introvert.”

More Stories

British military spy satellite launched – Business AM

Alarming decline in the Caspian Sea

Lithuania begins construction of military base for German forces